15 Jul Enhanced Flexibility in Our Classes

By Dave Smulders, Program Manager, Faculty Development at CTLI

But as soon as the dean started yesterday, I sensed trouble. He started talking about the need for the department to be more ‘flexible’ in its teaching. What the hell does that mean – yoga exercises at the beginning of each lecture? (Bates, 2019)

Last week, the good people at BCcampus organized a microcourse called Getting Started with Hybrid and HyFlex Learning. The course is micro in the sense that it’s a short offering — only a week long –with a mix of online synchronous (facilitator-led sessions conducted on the Big Blue Button video-conferencing platform) and asynchronous activities (threaded discussions and resource sharing). The course is part of BCCampus’s Facilitating Learning Online series of microcourses, courses, and webinars, and it drew attendance of about 70 educators from across Canada and at least one participant from South America. On my rough count, there were at least five of us representing the Justice Institute of BC.

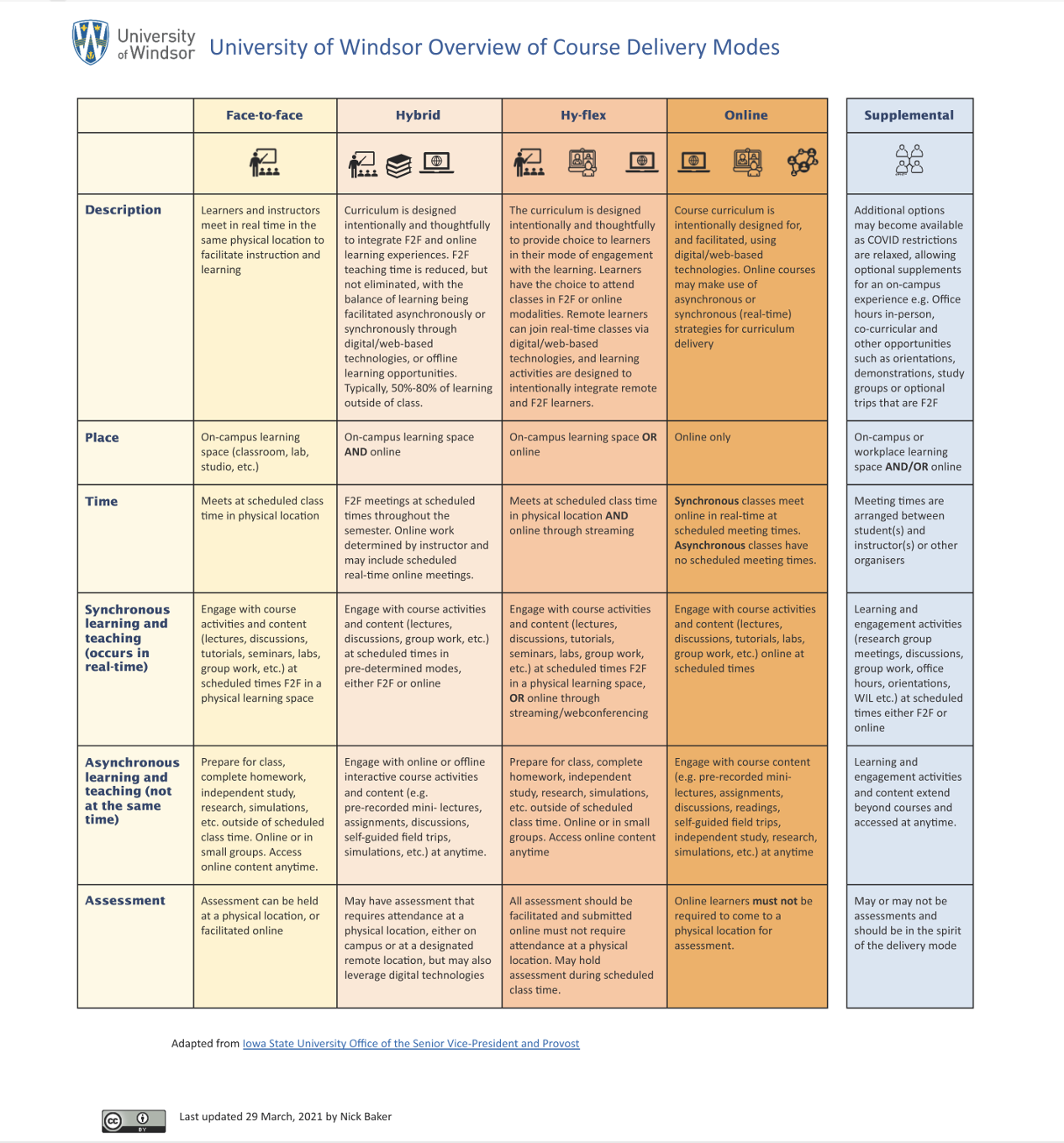

One of the first challenges for anyone wading into these discussions involves sorting out all the terminology. Many of these monikers, like hybrid, blended, and flipped learning, overlap with what is possible in both online and on-site teaching environments. Without worrying about which term currently reigns in the educational discourse, it is safe to say that the focus on this language suggests a renewed challenge to the orthodoxy of the traditional class with the instructor at the front somewhere between a podium and a whiteboard and a room full of passively attentive bums in seats. This particular challenge to what Paolo Freire (1970) called the banking model of education has been around for decades. The new twist comes in the form of our technological capacity to gather and connect in multiple media and formats. This comparative categorization by the University of Windsor will help you sort out the jargon:

Overview of Course Delivery Modes

Terms and Conditions

Readers might more readily recognize the term Hybrid to describe courses that combine elements of on-site and online learning activities. According to the Hybrid model, the focus is less on what information the instructor has to transmit over to the students and more about how students work with content that the instructor provides to them in a variety of media, from spoken word to written module to recorded videos and other curated resources (Saichaie, 2020). Under this definition, Hybrid reduces the importance of having a bum in a seat anchored to that so-called old way of teaching. So instead of a course where students are required to be in a classroom 3 hrs/week, the instructor redesigns the course so that maybe only they need an hour/week to gather and the rest of the time is devoted to significant learning activities that students can do together at their own time, whether online or somewhere on the campus, or maybe even at a mutually designated other location, like a library, a café or a park.

Hybrid Learning

The catch of Hybrid is that designated times are appointed for everyone. So if there is a session scheduled for Tuesday evening at 6pm, then everyone is expected to attend, no matter what else is going on that week. The HyFlex model, you might guess, takes Hybrid one step further in terms of flexibility by outlining learning opportunities that students can partake in via any number of mechanisms, from online to on-site. In this way, the Hybrid modelled is flexxed up, resulting in Hybrid Flexible, or HyFlex. Where Hybrid might identify equal learning opportunities, HyFlex purports to identify more equitable learning.

Visualizing Health Equity: One Size Does Not Fit All Infographic by RWJF on https://www.rwjf.org/en.html

So there still might be a session on Tuesday evening at 6 pm, but whether you attend in person in the on-site classroom or online via some kind of video-conferencing medium is up to you. In this model, no one misses a class because the inherent flexibility allows students to choose to be in class online or on-site. This flexibility spreads out from the content delivery to other aspects of any course – students working collaboratively, access to the instructor, completing assessments, etc. Everything is flexible in order to meet the needs of those concerned.

Get out your yoga mats! This sounds like a bending-over-backwards exercise in trying to please everyone. More futility than flexibility?

HyFlex Learning

Well, hang on a minute. It may not be that bad after all. Hybrid Flexibility, or HyFlex, is less about all things for all people (and all the extra work that requires) and more about creating multiple pathways to learning for students (Hayman, 2020). In this way, flexibility necessarily involves letting go a little bit and divesting some of your own control as an instructor over to your students. To be sure, this requires more work than one would take to develop a set of lectures to be delivered with no student engagement, but research has already supported the general direction away from teaching as stand-and-deliver content transmission toward something more engaging and engaged with greater involvement from learners. Active learning is effortful, and designing active learning is no slouch either.

Following the ideas of Universal Design for Learning and its known benefits to students (CAST, n.d.), Beatty (2019) defines the principles of HyFlex design as:

- Learner Choice: Provide meaningful alternative participation modes and enable students to choose between participation modes daily, weekly, or topically.

- Equivalency: Provide learning activities in all participation modes which lead to equivalent learning outcomes.

- Reusability: Utilize artifacts from learning activities in each participation mode as learning objects’ for all students.

- Accessibility: Equip students with technology skills and equitable access to all participation modes.

For instructors and course designers, these are the considerations that make HyFlex worthy of our attention. We have created an infographic to help our colleagues think through these principles as a way of identifying moments of flexibility in their course design (see below).

Not Just about the Tech

No one I know really wants to go through the experiences of large-scale course conversions from on-site to online classes the way we did last year in response to the conditions created by the pandemic. However, if there is a silver lining to that experience it is that having so many people all at the same time come to terms with how to continue to deliver high quality learning experiences for our clients (i.e. students) without the luxury of being able to all gather at once on our campuses. Similar to the internet boom of the late 90s and the surge of online courses back then, the transfer of entire programs and schools to switch their primary learning environments from on-site to online compelled us all very suddenly to confront our own pedagogical aims. What are we doing with our classes? What are our goals for learning? What do we expect of our learners? What is the best value for our learners’ time with us? These are questions of pedagogy, and it is a healthy response to try to answer those questions. Normally, if someone were to walk up to me and ask me about my pedagogy, I’d more likely to take my mother’s advice and stay away from weird people. But last year, you couldn’t talk about converting your courses to online without actually engaging on the topic of pedagogy. So yes, HyFlex involves a lot of questions about technology and modality, but it is primarily a question of pedagogy, and we need to be prepared to think informatively about how learning works and what we can best do as educators to support learning for our students.

Implications for Teaching

When we converted our JI courses from their environments in the classroom wing of the New Westminster campus and other bricks and mortar sites to Blackboard, we implemented a number of features that provided greater flexibility for students. For example, one instructor recently mentioned that they had noticeable success with online office hours in Collaborate, resulting in a greater uptake in student visits from the earlier model of the actual office. That’s HyFlex in action.

Just because we may be coming back to our classrooms and campuses in the fall and winter, that doesn’t mean we should abandon all we’ve learned from the past year about being more flexible for our students. Office hours is just one example, but that might be an easy place to start. There are other examples out there. Let’s harvest the best ideas from the past year and keep going. It’s not enough just to go back to the way it was, not when we’ve learned so much.

One thing we should be cautious about is the mistaken assumption that flexibility simply involves recording and posting everything you ever do in your classes which in effect leads to the replication of top-down practices of teaching. Again, re-thinking our classes is about re-design rather than reproduction of our content.

Professional Development Implications

Finally, back to the microcourse, and why you need to take note. Events like this are invaluable not only for staying current with good teaching and course design practices but also for discussing important ideas with fellow educators in other post secondaries around the province and beyond.

Many of these FLO events hosted by BCCampus are free. If you are reading this, then you have already demonstrated your interest in knowing more about best practices for educators. In that case, you should consider taking one of the FLO courses or attending an event. Often they are free of charge, but their value can’t be overstated. There are also opportunities to join in as a facilitator if you’ve got an idea you’d like to communicate to a wider audience.

If that is you, then consider contacting us at CTLI to discuss your idea. Maybe you can do a trial run with the JIBC community, and we’d love to help you put that on!