Learnings from Walking with the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh

Helen and Naz spend 2 days on a professional development retreat for post secondary educators and share about what they learned along the way.

July 2024 Vol.2 Issue 10

Assessments: Artefacts of a Culture of Learning

At the end of March, we hosted a workshop on trauma-informed teaching with Dr. Alana Abramson of Kwantlen Polytechnic University. Trauma-informed practice is something that has been familiar to JIBC for many years in fields like justice and health care. Our workshop was focused on trauma-informed practice in the context of teaching and learning. Dr. Abramson facilitated some fascinating conversations about trauma-informed pedagogy, and we considered effective practices to become trauma-informed educators.

A lot of the recommended practices we discussed focused on principles of good adult education: recognizing the diversity of learners in any given classroom, knowing ourselves, our biases, preferences, strengths, working towards safety and trust in the classroom, offering choice and remaining flexible in the face of variable conditions and demands. The workshop was an excellent reminder of our potential to have a positive influence on our learners. More broadly and perhaps even more importantly, representing an organization in the realm of public safety, JIBC educators also have a responsibility to see ourselves as helpers and supporters, just as we expect of our learners.

One of the key takeaways from this workshop, for me, was that trauma-informed practice in education sits well as an aspect of the JIBC teaching and learning culture. We all share the responsibility of helping and serving our learners. This includes not only the instructors in the classroom but also those who have other non-teaching roles, such as in the Registration and Student Services offices, the Office of Indigenization, the Library, the Centre for Teaching, Learning and Innovation, the Writing Centre and other services that make up our support network. As educators we are in the service industry, not in the sense of satisfying customers, but more accurately as those who work to help others who are in need. We are at the service of our learners.

In her study of mindsets, Cultures of Growth, Mary Murphy (2023) relays the story of two versions of high stakes assessment she witnessed as a student at Stanford. Presentations for most students are nerve-wracking; however Murphy noticed a remarkable difference between two types of environments in which those presentations were delivered. She describes one scene where grad students were given public dressing-downs by hyper competitive professors who seemed more interested in scoring points with their withering criticisms than in helping students to learn. She then describes an alternative scene where students similarly presented to professors, only in this scenario, students received feedback that professors delivered with the intention to improve the students’ research. In both cases, students were stressed and nervous. In the second scenario, students left the seminar feeling motivated and keen to continue working on their research to make it better. However, in the first scenario, students seemed to fall apart, both on the stage and afterwards, feeling dejected, demotivated and confused. In which of these two scenarios can you see a stronger connection to learning? And yet, many would argue that the first scenario is good, rigorous scholarship and education. Murphy made it her business to investigate the cultures that directed these conflicting mindsets.

What is striking about Murphy’s anecdote is how demonstrative this assessment is of the academic culture in which it occurred. Surviving the assessment served as a kind of rite of passage for students. If you got through it, you were deemed a success, and at some point in the distant future, you might even be invited to join the panel of evaluators, thereby perpetuating the culture of genius that Murphy describes in her book where performance is valued as a hallmark of achievement and mindsets are fixed. This reflects a culture of win-lose results that leaves little room for discovery and growth.

In their book The Art of Evaluation, Fenwick and Parsons (2009, 158) liken this mentality to the “hero’s journey” version of education, a distinctly North American industrialized paradigm, whereby learners find themselves beset with challenges, obstacles, and barriers that they can only overcome through a combination of individualistic persistent effort and natural talent. This approach produces many winners, those equipped to meet the challenge, but many more losers, who decide that the pain, embarrassment or trauma of failure and humiliation is simply not worth it and who may decide that learning is not an experience worth cultivating. As a system, this seems to function as intended, but it’s not clear that the costs of such success are worth it. Moreover, in this paradigm, learning is presumed to be the antidote against attack. Is this the metaphor we want for learning where assessment becomes punishing and punitive, designed to perpetuate a state of haves and have-nots? Surely, there is a better way.

Fortunately, helpful alternatives are in abundance. Murphy, for one, advocates for the “culture of growth” approach. She argues that we have bound up our evaluative practices into such a constrictive, rigid mindset that any mention of assessment can instantly drive up the anxiety levels. Also, assessment that is based exclusively on performative excellence tends to shut out opportunities to learn. People will choose to play it safe in order to achieve a minimum standard of competency rather than take a chance or experiment with an idea. This is contrary generally to the spirit of adult education that seeks to support and cultivate learners. Murphy offers several alternative examples where individuals and groups who listen to and incorporate evaluative feedback for their proposals invariably end up with more robust and effective ideas that get translated into success plans and products. Through the lens of the fixed mindset, the need to incorporate feedback may look like failure, when individuals are encouraged to rework their ideas and adopt advice, though in the long run the results begin to speak for themselves. In the Culture of Growth, educators do not shy away from providing challenges for or demanding rigor from their learners; however, when rigor is matched with a belief in student success, there is more likely to be a positive and productive learning experience.

The pieces in this issue of the Learning Hub constitute a partial attempt to collect some helpful ideas about assessment, their design and implementation, and some discussion about how assessment fits into the bigger picture of education. We do not promise to offer clear solutions to the challenges of curriculum design and fitting assessment into that picture. We do seek to raise a few questions around those challenges and consider some recent experiences that have added further perspectives to this general discussion. Through this issue, we advocate for the idea that education design is a creative endeavour and we need to broaden our imaginations if we want to go beyond the status quo and make positive change in our work. In this way, we acknowledge the argument by the record producer Rick Rubin that we are all living as artists, whether we know it or not. “We perceive, filter, and collect data, then curate an experience for ourselves and others based on this information set.” Finally, we hope you will be able to take in these ideas and add them to your own understanding of assessment.

References

Fenwick, T. J., & Parsons, J. (2008). The art of evaluation : a resource for educators and trainers (2nd ed.). Thompson Educational Pub.

Murphy, M. (2024). Cultures of growth : How the new science of mindset can transform individuals, teams, and organizations. Simon & Schuster.

Rubin, R. with N. Strauss (2023). The creative act. A way of being. Penguin.

Land Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge that we work from the New Westminister campus which is located on unceded traditional territories of the Qiqéyt (Qayqayt), xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam) and Coast Salish Peoples. This is a land where the river meets the great sea and the mountains overlook the vast and fertile valleys. This is a land of confluence and crossovers, connecting people, cultures, and ideas. We are grateful to learn about the history of these lands and to join in new traditions.

Wednesdays Faculty + Staff Drop-ins NW Campus (CTLI Office) AND

Thursdays Faculty + Staff Drop-ins Online:

Our weekly drop-ins will be taking a place online on Thursday@ 12:00 pm – 1:00 pm. Please Register in advance for the next upcoming sessions.

Save the Date! DEMOFEST is coming back for 2024!

Held over 2 days, October 22 and 23rd, join us virtually and in person as we showcase what everyone has been up to for the last couple of years. Stay tuned as we finalize details!

In this episode, Dave invites Christina Bahr and Junsong Zhang into the studio to talk about their current project, a full program redesign of the Associate Certificate in Applied Leadership. Join them as they talk about turning the whole process on its heels, what that means, and how participating in this new way impacts how they look at assessments.

Show notes from this episode:

The Applied Leadership Certificate redesign team involves a cast of contributors including the following designated “helpers”:

Helpers from outside JIBC:

JIBC staff who also attended meetings and contributed to the discussions and process:

With every issue of our Learning Hub, we imagine you reading it with a soundtrack (because aren’t we all just main characters in our very own movie?). Here’s this issue’s mixtape, curated by our very own Dave. Enjoy!

Helen and Naz spend 2 days on a professional development retreat for post secondary educators and share about what they learned along the way.

Learn about what equity-minded assessments are and how to design your own equity-minded assessments.

Albertine shares what she learned from attending Dr. Candyce Reynolds presentation on ePortfolios and Reflections.

While assessments are always a challenging time for students, there are a few things that JIBC can do to reduce those barriers. Kavita shares how we at JIBC could focus on reducing the cognitive, motor, and physical load for students and try to provide an equivalent experience for all learners.

A Comprehensive Guide to Applying Universal Design for Learning | A Collection of Three UDL

Workbooks. Dave draws more on how to apply Universal Design Principles (UDL) to assessment design.

Read about how AI has the potential (good or bad) to impact the way students tackle assessments.

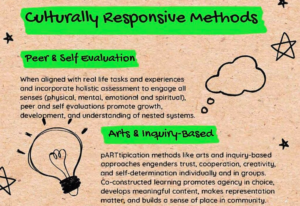

Including Indigenous knowledges into education systems occupying Indigenous lands is an act of Truth and Reconciliation. Heather shares culturally responsive methods to indigenize assessments.

For this issue on assessments, we asked our community:

Could you share any innovative or experimental assessment methods you’ve tried in your courses, along with any lessons learned from these experiences?

In what ways do you incorporate authentic or real-world assessments into your courses, and how do you assess skills such as critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity?

Below are their recommendations.

Currently not teaching. Supporting a program of short courses, which culminates in a high-stakes assessment at the end.

Could you share any innovative or experimental assessment methods you’ve tried in your courses, along with any lessons learned from these experiences?

What is innovative? …we’ve worked on splitting large assessments into smaller pieces. We’ve set up some parts so that they can be submitted via video OR written (to support different comfort levels).

In what ways do you incorporate authentic or real-world assessments into your courses, and how do you assess skills such as critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity?

Use of self-reflection, BUT we don’t set that up well enough I think…. We do role-plays, which is a GREAT learning experience, BUT is costly in terms of time and coaching/instructional resources. We were just chatting in the hallway about an assessment: a rubric to assess on process is VERY different than a rubric to assess on approach/reaction. What are we trying to do and how do we communicate that to instructors?

Currently program managing but will return to PCP in August.

Could you share any innovative or experimental assessment methods you’ve tried in your courses, along with any lessons learned from these experiences?

1-1 question asking, I use the socratic method. Kahoot quizzes, to help students do formative assessments throughout courses. Skills drills to assess and help students assess their competence. Requesting students provide their understanding of topics in a non-conventional way. For example, creating skits, scenarios, stories or create a meme or gif about how pathological processes or physiological processes progress.

We will sometimes ask students to show us their learning by defining what a topic isn’t. An example might be What isn’t a good way of building rapport? This could be an example they’ve experienced, witnessed, or seen on TV. Allowing students to discuss their own lived experiences in the context of the material helps them retain the knowledge and build connections with the material.

In what ways do you incorporate authentic or real-world assessments into your courses, and how do you assess skills such as critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity?

Encouraging students to ask questions, individually or to the group has improved their ability over the course/program to build their critical thinking skills relating to the material.

I believe creativity is present in everyone, and my role is to provide opportunities where students feel safe and encouraged to display theirs.

Scenarios, skits or asking students to provide media that supports the goal allows students to display this in whatever medium or degree they feel comfortable to.

When we encourage that type of environment, students are more likely to work collaboratively which helps them in the workplace later!

My preferred way to determine success is to ask the students. Do they feel successful? Do they feel they’ve gotten better at problem solving? How does the student perceive their learning journey?

If a student feels they have, then that confidence will help them build the skill.

Courses in leadership (LEAD) and training and facilitation (INDC)

Could you share any innovative or experimental assessment methods you’ve tried in your courses, along with any lessons learned from these experiences?

The courses I teach are rather tightly scripted, and they do not include summative assessments (for grades). That said, I look for opportunities to casually weave in formative assessments including self-and peer-assessments. I often embed them into activities such as brainstorming. I might prompt learners in one group to “brainstorm and write down ideas” about a topic, such as approaches to facilitate an aspect of a difficult conversation, while those in a second group are invited to “brainstorm and write down ideas, and don’t stop until you’ve got at least 10”. As the two groups share their lists, they often find that the second group generated more, and more creative, options. One of the purposes this serves is to remind both groups that with intention and a bit of structure (“don’t stop until you’ve got at least 10″), they arrive at more good options to choose from. A little activity like this may also serve as a pre-assessment, such as in a lesson on courage or integrity. When someone from the first group shares, “I wanted to keep coming up with more ideas,” yet their group only offered a few, this can be a powerful starting point for a class conversation on what it takes for any of us to act bravely, such as when we have an idea that could benefit a process or outcome. In short courses (2-3 days) with no follow-up, I do wonder, however, how much of students’ learning actually translates into bolder behaviours in the ‘real world’. (I would love to take time to examine in what ways we might tap into Kirkpatrick Levels 3 and 4 — which is where the ultimate value of learning lies, for the learner’s organization and its clients.)

In what ways do you incorporate authentic or real-world assessments into your courses, and how do you assess skills such as critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity?

I think a simple proxy for creativity is time. Wasn’t one of Einstein’s suggestions to stick with challenges longer in order to arrive at better solutions? Some of the LEAD classes end with learners working in triads to make meaning, and contextualize, learning from the day. This is the last activity of the day, and in the online environment, I can see how long different triads stay in a conversation before they log off. Some leave early, some stay until the scheduled class end time, and some stay connected past that time. We each have an approach to learning, and sometimes we are tired at the end of a long day. The point I sometimes make with classes the next morning is, whether you engaged with the task (make meaning and contextualize learning) as part of your assigned triad, or on your own later in the day or the next morning, your results (fresh insights, commitment to implementing new skills) will likely be more powerful when you engage with the task more (in whatever way works for you). A few learners often validate this notion when they share personal experiences of staying with a problem longer.

Please get in touch with your Liaison Librarian if you need any help!

Do you want to celebrate the success of a friend or colleague here in our world of teaching and learning at JIBC? Let us know and we’ll make a space on these pages.

The Learning Hub is a production of the good folks at the Centre for Teaching, Learning, and Innovation (CTLI). We welcome ideas and suggestions for edition themes and ideas for articles. Contact us at ctli@jibc.ca.