Equity-minded Assessment

- 3 mins read

Download an alternate text format

Equity-minded Assessment (PDF) article.

Designing courses depend upon the clear alignment between learning outcomes, learning activities and assessment strategies. This in itself is a considerable task in the curriculum development process. Additionally, in recent years, educators have become much more mindful of the type of assessment to include in this alignment, giving much more attention to questions of inclusion and equity. As it turns out, a sharper focus on inclusion and equity helps ensure that assessments maintain rigor and depth while being more available and practical for a wider variety of students.

What does it mean to design an equity-minded assessment?

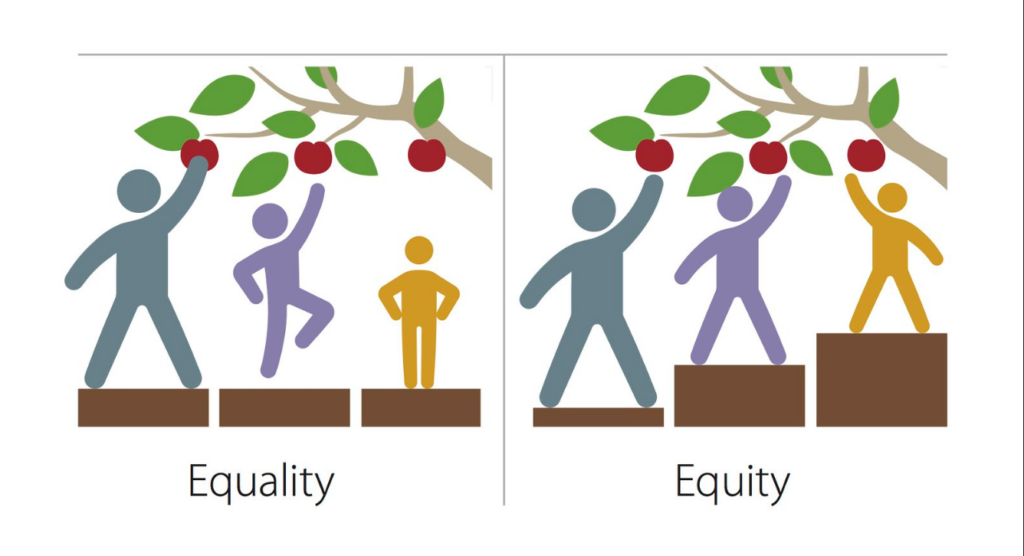

Equity involves the heightened realization that each student brings a unique background and set of experiences to the classroom, and success is not predetermined by a student’s identity or social history. Therefore, by taking a position to be equity-minded, we work to ensure the learning success of all students toward the achievement of a course’s stated learning outcomes. This does not mean the same as “treating everyone equally” which implies an equal standing among all students. Instead, we recognize and validate differences in backgrounds, knowledge, identity, ways of learning and knowing.

Equity-minded design overlaps with several other perspectives in the educational environment, depending on how one approaches course design work. Some educators will recognize equity-minded design as upholding principles of trauma-informed practice, particularly as applied to teaching and learning contexts. Others may recognize characteristics of culturally responsive teaching and Indigenization practices, as well as inclusive teaching. Course designers who apply principles of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) will also recognize equity-minded principles in their own assessment design practices. These are all concepts that can be seen as interweaving, with each bringing a different but important focus but working toward a common goal of helping all students succeed in their efforts to learn and develop their skills and knowledge.

How will I recognize an equity-minded assessment?

We should acknowledge that equity-minded design can apply to the process of design as well as the final products in the assessments themselves. This process involves the designers recognizing their own biases and limitations in conjunction with the invitation to students to participate in the design process. Assessments that are produced in this manner are more likely to be more equitable and coherent as a result, as well as demonstrating the following characteristics:

Cultural relevance and sensitivity to the diverse backgrounds and experiences of students. This includes incorporating examples, language, and contexts that are familiar and accessible to all students.

Use of reviewing rubrics to identify and eliminate biases that could disadvantage certain groups of students. This involves ensuring that assessment content is relevant, fair, and free from stereotypes or cultural assumptions.

A focus on continuous improvement rather than correction or punishment. Equity-minded assessment is an ongoing process that involves reflection, evaluation, and continuous improvement.

Recognizing limitations and mistakes of the past in educational systems and structures that served to reproduce power imbalances among different groups of people based on their identities.

Clear and transparent criteria provided to students to help them understand what is expected of them in assessments. These criteria can be used to inform a grading rubric.

Provision of timely feedback. This involves providing constructive feedback at the right time to help students understand their strengths and areas for improvement, and in a way that empowers them to take ownership of their learning.

Variety in the use of measures to capture the diverse strengths and abilities of students. For example, projects, portfolios, presentations, and performance assessments.

Prioritizing accessibility for all students, including those with disabilities or learning differences. This may involve providing accommodations, such as extended time or alternative formats, or designing so that accommodations are not necessary, to ensure that every student has an equal opportunity to demonstrate their knowledge and skills.

As you develop your assessments, it is important to be able to review your own practices and design choices so that your assessments not only align with your teaching, but you hold yourself to the same standards that you expect of your students. Like any industry, the educational practices we grew up with have evolved over time taking into consideration new ideas, research discoveries, and evidence-based practices. Sometimes it is difficult to break away from the systems and structures that we came through ourselves as students. But if we recognize that those systems were not perfect to begin with, then we can begin to think more creatively and openly about how to improve our practices, and equity-minded design offers good ideas in that direction.

Change to assessment does not need to happen all at once. It is possible to improve courses over time with thoughtful revisions and adjustments taking all of the above into account and committing to staying in touch with educational developments in the areas of teaching and instructional design.

Further reading

There is a lot to read on this topic, from a number of angles. Below are some suggestions that can help you look at equity as it applies to our work as education developers, administrators, and instructors. I want to thank Heather Saranczak from the Office of Indigenization in particular for her generosity in sharing ideas and resources.

Addy, T. M. (2021). What inclusive instructors do: Principles and practices for excellence in college teaching (D. Dube, K. A. Mitchell, & M. E. SoRelle (Eds.); First edition.). Stylus Publishing, LLC.

Alberta Education (2005). Assessment: Authentic Reflections of Important Learnings. In Our Words, Our Ways: Teaching First Nations, Métis and Inuit Learners, pp. 111–122.

Artze-Vega, I., Darby, F., Dewsbury, B., Imad, M. (2024). The Norton Guide to Equity-Minded Teaching. Norton. *Educators can request a free ebook copy.

Brown, C. (n.d.) Equity and Assessment. Centre for Professional Education of Teachers.

Equity and Assessment. Centre for Professional Education of Teachers.

Equity in Assessment. (n.d.) National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment.

Hogan, K. A. (2022). Inclusive teaching: Strategies for promoting equity in the college classroom (V. Sathy (Ed.); First edition.). West Virginia University Press.

Lorenz, D. (2013). Dream weaving as praxis: Turning culturally inclusive education and anti-racist education into a decolonial pedagogy. In Education, 19(2), 30–56.

eCampusOntario (n.d.). Culturally Responsive Assessments. In Designing and developing high quality student-centred online/hybrid learning experiences.

Williams, S., and Perrone, F. (2018). Linking Assessment Practices to Indigenous Ways of Knowing. National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment.