Mary DeMarinis & Lisa Middleton

About Mary

Mary is the Registrar and Director of Student Affairs at the Justice Institute of British Columbia. She has over 30 years of experience in the area of student services in the post-secondary sector with an interest in ensuring fair and equitable access for all students, but with a history of advocating for better access for marginalized individuals. Mary has a BA (UVIC), MA(UBC), MPA(UVIC) and is currently a EdD student at UBC in Educational Leadership and Policy. Mary’s main areas of research are related to social justice, and public policy and inequality.

About Lisa

I have 20 years of experience in Student Services and I always seek to understand the issues and find creative solutions for the problems that our students face. With a BA in Anthropology and an MFA in Creative Writing – both from UBC – I am always willing to challenge my own bias and interrogate how our organizational culture and practices can better represent the diversity of our students.

Gender Nomenclature at JIBC

The registrar team at JIBC has been invited to contribute to this edition of the Learning Hub, which is all about equity, diversity, and inclusion. This is a subject that is important to us and we feel grateful to be asked and we also find that we have something valuable to contribute – the challenge was to narrow the focus so that our contribution would be meaningful for the JIBC community. We’ve chosen to write the story about gender nomenclature at JIBC and to share with you upcoming opportunities for all of us to learn more about how we collect gender in the system, why it’s important, and how this is a good first step in supporting gender diverse students at JIBC.

As many of you will remember, JIBC was one of the first institutions in the province to include an alternate gender category on their paper applications. At the time, we used the letter T as a category that was very much ahead of the rest of the province. Since then, our applications have moved over to the electronic world, and on to a centralized, ministry supported portal – Education Planner BC (EPBC). This required us to conform to the ministry standard and collect and report gender in a traditional, binary way, male or female. This has been a concern for many, including the Ministry, and especially for JIBC registrar’s team for several years.

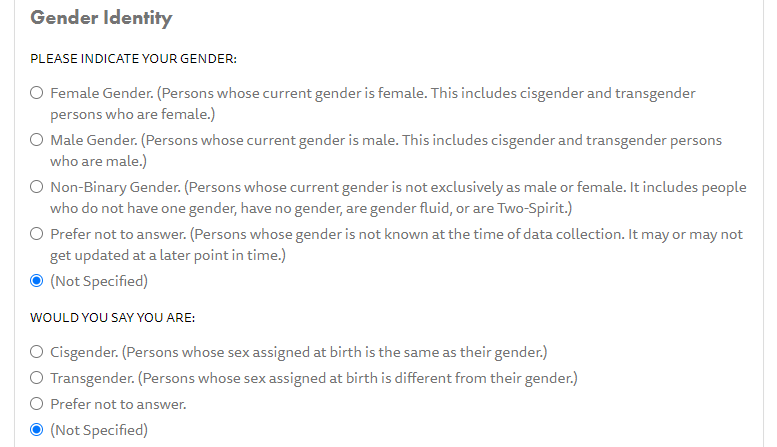

The practice of limiting gender in such a binary way excludes and marginalizes those that don’t identify as male or female. This binary discourse creates environments where trans students feel they don’t belong and contributes to, what Nicolazzo (2017) has termed, “trans oppression” (p.8). Students, special interest groups, and Registrars across the province were advocating the Ministry for changes in how we collect gender, and it has finally had an impact. In April of this year, the Ministry released their new Gender Identity and Sex Information Data Standards. This provides opportunity for Post-Secondary institutions to ask students two questions on the application – see screenshot below of what is now appearing on the JIBC application on EPBC.

As with our earlier adoption of T on our applications, JIBC has been the first public post-secondary to ‘go live’ with the new standards. JIBC began collecting gender in a non-binary fashion on the application for programs in July, a development welcome by your Registrarial team. Work is now underway to adopt these standards on Instant Enrolment, the system students use to register for our shorter courses. We anticipate this work to be done early in the new year. We will also be working with all program areas who offer contract activity to review how they are collecting this information to allow our contract students to declare themselves this way as well. The technical changes in how and where this information is stored in Colleague are minimal, but critical in terms of how that information flows out to other systems like Blackboard. Training of staff will be undertaken as part of this comprehensive project.

We are conscious of the fact that there may not be a shared comfort level with these new gender standards so we will be hosting several information sessions throughout December and January to review the standards and to talk about how important this is not only for our students, but also to meet the goals of our strategic plan priorities related to equity, diversity, and inclusion. Watch for our announcements and join us to speak more about the student experience as it relates to gender identity.

The Shift in Understanding Gender

The change in how we are collecting information is a reflection of how the idea of gender has shifted and is an important contribution to social justice.

Western civilization is founded on the notion that gender is binary. Individuals were born with either female or male genitals that defined their sex, and thus, their gender. Anyone who did not align with their sex assigned at birth, or who did not align with heterosexism was considered deviant (Renn, 2010). This deviance was historically described as a disease (Levin, 2019), a behaviour that violated fundamental religious beliefs (Renn, 2010), or a criminal act (Lugg & Murphy, 2014). Individuals who were labelled by society as sexually deviant were either treated for their pathology, incarcerated, or ostracized from society, and sometimes all of these together (Spade, 2014). Those defined as deviant have been subject to many forms of violence and indignity (Nicolozza, 2017). Those included in this definition were lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgendered (LGBT) or otherwise known as the Queer community. These individuals have lived with intense cultural hatred and have dealt with medical, legal, and political oppression (Lugg & Murphy, 2014; Nicolozza, 2017).

Members of Indigenous communities and anthropologists have long argued that the western understanding of gender is rigid and is not shared by many Indigenous cultures. In Canadian and American Indigenous cultures there were individuals who were identified as two-spirited, a term that recognizes the intersection of identity, and includes sexuality, gender, culture, community, and spirituality (Wilson, 1996). This notion has helped to advance the understanding that gender is socially, and politically constructed in western society. Further gender research throughout the 70’s and 80’s increased the visibility and legitimacy of non-heteronormative genders (Renn, 2010; Lugg & Murphy, 2014).

The human rights movement of the 60’s and 70’s advanced many rights-based agendas including the rights of the Queer community. The removal of homosexuality from the criminal code in Canada in 1969 was a result of the shift in social values in Canadian society and removed the criminality of homosexuality (Kimmett & Robinson, 2001). In 1973, homosexuality was removed from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), but replaced with a lesser pathology that indicated homosexuals were still in conflict with their sexuality and thus needed to be treated (Burton, 2015). It wasn’t until 1987 that homosexuality was completely removed from the DSM (Levin, 2019). These changes alongside a ground swell of activism, and an increase in gender-based research contributed to the paradigm shift related to gender. It helped to define the differences between sex assigned at birth, gender identity, gender expression and sexual preference (Scott & Dennis, 2017).

More recently, Canada has experienced several changes that have furthered the gender-diverse agenda. In 2016, Canada passed Bill C16 which added gender expression and gender identity as protected grounds to the Canadian Human Rights code and to the Criminal code related to hate propaganda (Department of Justice, 2017). What this means is that the rights of transgender or gender diverse individuals are now protected by legislation. In a 2017 landmark human rights case, a trans activist successfully argued that there had to be a legitimate reason to collect sex and/or gender information by governmental agencies (Canadian Human Rights Commission, 2017). This case sets a new standard on how, and why, gender and/or sex information is collected. All governmental agencies need to reflect on whether there is a legitimate rationale to collect the information and if there is, there is increased scrutiny on how the information is collected, protected, and used.

Most of these changes have advanced the agenda for some of the members of the queer community, namely lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals (LGB). While these changes have increased the legitimacy and visibility of LGB individuals in Canadian society the same is not true for trans individuals. Spade (2014) argues that trans people must strongly consider why these changes have not resulted in the same level of change for their community. While there have been some advances in how Canadian society understands gender, oppression towards the trans community remains (Spade, 2014; Nicolazzo, 2017).

If institutions want to respond to the shifting paradigm around gender and contribute to the liberation of trans students they will need to examine how they are complacent in maintaining the oppression. Post-Secondary institutions are well positioned to advance the gender agenda and contribute to the liberation of those that are gender oppressed by first and foremost collecting gender in a non-binary way. Institutions fail trans students if they do not expand the gender categories and then use the data to develop campus services relevant to the trans community. Garvey et al. (2020) suggest that the intersectionality in the lives of trans students complicates how they can find supports on campus. Trans students can also have a disability, be from a specific ethnic background, or have a special interest. They can struggle to find community in any one of these identity-based support areas on campus. (Garvey et al., 2020). Researchers argue that institutions need to consider, and embrace the intersectionality of race, ability, and gender when developing services (Garvey & Rankin, 2014; Nicolazzo, 2017; Garvey, et al., 2020). However, this is not enough. Institutions must also have policies that are inclusive and accessible at the institutional level (Nicolazzo, 2017). Additionally, there must be a commitment at the institutional level to include diversity in the strategic plan that can be translated into action plans that help shift both culture and understanding of gender fluidity (Garvey et al. 2020).

Conclusion

Post-secondary institutions are understood to be places of higher learning where knowledge is both consumed and created. Renn (2010) describes a central paradox for the queer community as it relates to the post-secondary environment. While much of the queer theory research is generated in the post-secondary system, the system is “substantially untouched by the queer agenda” (Renn, 2010 p. 132). Renn (2010) goes on to describes this paradox as it relates to the tenure and promotion track for faculty members but the idea can be directly applied to gender nomenclature in the post-secondary environment. While post-secondary institutions are one of the places where information is created that is advancing our understanding of the trans community, until recently they are unable to make the pragmatic shift away from the binary definitions in how they collect gender. Garvey & Rankin (2020) suggest that the post-secondary environment is often the place where individuals recognize and accept their gender identity. While there has been some shift in our understanding of gender diversity it is still unsafe in society for people to live their true trans identities (Nicolazzo, 2017). Institutions have good intentions and have created a discourse that is attempting to shift our understanding of the needs of gender diverse students, but there is much work to do (Garvey et al, 2020)

While institutions are well intended they need to reform the way in which gender is collected and give authority to the student to share, and change their gender as they choose. Along with trickle up policy planning, knowledge activism which transforms knowledge into action will be required (Gilles, 2014). Institutions will need to be informed but they will also need institutional courage to persuade the government that the time is now to make the change. This literature review has confirmed that shifting how gender is collected at the post-secondary level is morally the right thing to do. If not, the sector remains “complicit in trans oppression” (Nicolazzo, 2017, p. 18).

References

Burton, N. (2015). When homosexuality stopped being a mental disorder. Psychology today, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/hide-and-seek/201509/when-homosexuality-stopped-being-mental-disorder

Canadian Human Rights Commission (2017). Trans activist settles human rights case about gender collection. https://www.chrc-ccdp.gc.ca/eng/content/joint-news-release-trans-activist-settles-human-rights-case-about-gender-collection-1

Department of Justice (2017). Bill C-16: An act to amend the Canadian human rights act and the criminal code. https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/csj-sjc/pl/identity-identite/statement-enonce.html

Dockendorff, K., Nanney, M. & Nicolazzo, Z. (2020). Trickle up Policy-building: Envisioning possibilities for Trans*formative change in post-secondary education. In In E. M. Zamani-Gallaher, D. D. Choudhuir & J.Taylor (Eds.) Rethinking LBGTQIA Student and Collegiate contexts: Identity, policies and campus climate. (pp.153-168). Routledge.

Garvey, J. & Rankin, S. (2014). The influence on outness among trans-spectrum and queer-spectrum students. Journal of Homosexuality, 62, 374–393, https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2014.977113

Garvey, J., Kennedy, B., Dews, S. & Greene, R. (2020). Gender, kinship, and student services: A dialogue centering trans narratives in higher education. In E. M. Zamani-Gallaher, D. D. Choudhuir & J.Taylor (Eds.) Rethinking LBGTQIA Student and Collegiate contexts: Identity, policies and campus climate. (pp. 27-44). Routledge.

Kimmett, D. & Robinson, D. (2014). Sex, Crime, Pathology: Homosexuality and Criminal Code Reform in Canada, 1949-1969. Canadian Journal of Law and Society, 16(1), 147-165. https://doi.org/10.1017/S082932010000661X

Levin, A. (2019). Courageous Actions Led to removal of homosexuality as a diagnosis from the DSM. Psychiatric News, https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.pn.2019.10b11

Lugg, C. & Murphy, J. (2014). Thinking Whimsically: queering the study of educational policy making and politics. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 27(9), 1183-1204,https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2014.916009

Nicolazzo, Z. (2017). Imagining a trans* epistemology: What liberation thinks like in postsecondary education. Urban Education, 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0042085917697203

Renn, K. (2010). LGBT and Queer Research in Higher Education: The state and status of the field. Educational Researcher, 39(2), 132-141, http://www.jstor.com/stable/27764565

Spade, D. (2014). Normal life: Administrative violence, critical trans politics, and the limits of law (2nd ed.). Duke University Press.

Scott, K. & Dennis, D. (2017). Being Seen Being Counted: Establishing expanded gender and naming declarations. BC Council on Admissions and Transfer. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED586104.pdf

Wilson, A. (1996). How we find ourselves: Identity development and two spirited people. Harvard Educational Review, 66(2), 303-317.

Want to chat more with Mary and Lisa? Reach out to them at mdemarinis@jibc.ca and lmiddleton@jibc.ca.